HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF EDGEFIELD, SC

In the antebellum era, Edgefield was not the market town of the District. In the Plantation economy, the plantation owners took their cotton to market in Augusta or Hamburg and bought the majority of their supplies from merchants in those market towns. The merchants of Edgefield Courthouse Village primarily filled in the needs of the planters between trips to the larger market towns.

During the first several decades of the nineteenth century, Edgefield, being the courthouse village of a large and prosperous District, began to develop its reputation as a center of law and politics. A number of the sons of the wealthy cotton planters and other ambitious young men, after attending elite schools and colleges across the nation, came to Edgefield to practice law and engage in politics. Many of these young lawyers and politicians also maintained large plantations out in the District. These budding leaders built substantial houses in town and created a social atmosphere which attracted more similarly-situated young men.

The social prestige of being a planter with broad acres and many slaves, and dabbling in law and politics, caused many ambitious young Edgefieldians in the antebellum period to develop a self-confidence, an over-developed sense of honor and an aristocratic world view which did not always serve them well. One result of this was a widespread devotion to the Code Duello which resulted in a number of Edgefield’s best and brightest becoming involved in tragic duels. Another result was a sense of invincibility which caused many to approach war with a cavalier attitude and to focus on the glories of victory rather than on the horrors of death and defeat. These young men also accepted violence, which had been a common occurrence in Edgefield from its earliest days, as an inevitable part of life, and in some cases even glorified it.

While planting, politics and violence captured the imagination of most white Edgefieldians, a number of other bright young men looked for opportunities in industry and commerce. Dr. Abner Landrum developed a pottery industry which was to have a major impact on Edgefield for more than half a century. Henry Schultz, a German immigrant, developed Hamburg, a new town on the Savannah River which became an important commercial center during the antebellum era. Another German immigrant, Christian Breithaupt, built the first textile mill in this part of the state at Vaucluse. A number of Edgefieldians participated in bringing the South Carolina Railroad to Hamburg. The Plank Road from Edgefield to Hamburg was built. William Gregg, a Charleston silversmith, came to run the Vaucluse factory and wound up developing the Graniteville factory, the most successful textile operation in the antebellum South. These industrial and commercial enterprises were a significant part of the fabric of antebellum Edgefield and a number of the Edgefield lawyers and planters were involved in these endeavors.

However, the most significant contribution of antebellum Edgefield to our nation’s history was the intense sectionalism which began in the mid 1820’s and evolved to 1860. Edgefield Congressman George McDuffie initiated the fight against federal tariffs which were imposed on imported goods to protect New England manufacturers. He believed that the interests of this section of the country were being sacrificed for the good of New England.

McDuffie, together with South Carolina statesman John C. Calhoun, developed the doctrine of “nullification” which postulated that a state had the right to nullify a federal law with which it disagreed. This doctrine was put to a test in 1832. South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Nullification, and President Andrew Jackson threatened to send troops to the state to enforce the tariff. Edgefieldians, like most South Carolinians, reacted violently to the President’s threats. Militia units were called up and the state braced for war. A national crisis was averted only by a last-minute compromise that gradually reduced the tariffs.

One of the most significant developments of the first half of the 19th century was the migration of settlers from the older states of the South and particularly from South Carolina and the Edgefield District to the newly-opened areas of Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. Among the pioneers in this movement were two Edgefieldians, William Barrett Travis and James Butler Bonham, who entered the fight for Texas Independence from Mexico and who died at the Alamo in 1836.

A decade later, as war broke out between the United States and Mexico, numerous young Edgefieldians joined the war effort by becoming members of the Palmetto Regiment from South Carolina. This regiment was at the forefront of the American forces and was the first to enter Mexico City in 1848. Although the casualties of young Edgefieldians in this war were appalling, those who survived were greatly celebrated and honored. The glorification of the Palmetto Regiment soldiers and the Mexican War was perhaps, in part, responsible for the attitude of Edgefieldians and South Carolinians in 1860 who were enthusiastic supporters of Secession and war.

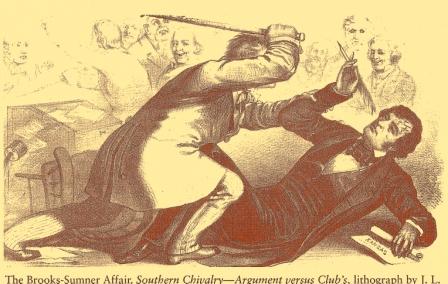

As the anti-slavery movement gained momentum and began to threaten the economic basis of the South’s prosperity in the 1840s and 1850s, most white Edgefieldians, like most white South Carolinians, embraced the sectionalism which had developed during the Nullification crisis. National unity was severely threatened in 1850 when many leaders throughout the South began to speak of Secession. The 1856 caning of Senator Charles Sumner by Edgefield Congressman Preston Brooks on the floor of the United States Senate galvanized the nation and set South Carolina on a course for Secession and Civil War. By the fall of 1860 when Abraham Lincoln was elected President, all but a few Edgefield citizens were convinced that the time had come for the South to go its own way. A convention was called and Edgefield’s delegation joined in the unanimous declaration of secession.

At the outbreak of war in April of 1861, the vast majority of Edgefieldians welcomed the conflict, believing that they would defeat the North in short order and the risk of slavery being outlawed would be eliminated. Hundreds of Edgefieldians volunteered for service and were quickly sent to Virginia to take on the federal forces. Little did they realize the sacrifices which they would make during the ensuing four years. Before the war was over almost every Edgefield male between the ages of 15 and 60 had been involved in some way in the war effort. Although the war never got closer than Aiken (Edgefieldians have always claimed that Sherman was afraid to come to Edgefield!), the people of Edgefield endured four of the bloodiest years of war in human history in which nearly one-third of their fighting age white males became casualties. The incalculable devastation of the war is hard to comprehend. Almost all the liquid assets of the citizens had been invested in Confederate currency or bonds which were now worthless. The emancipation of the slaves wiped out a huge portion of the County’s wealth, thrust most people – black and white – into dire economic straits and necessitated an almost total reorganization of the political, economic and social systems.

During the eleven year period of Reconstruction, the newly freed slaves, called “Freedmen,” became “sharecroppers,” farming the land on shares with the landowners. They also acquired the right to vote and hold office. Together with “Carpetbaggers” (Northerners who had come South seeking opportunities) and “Scalawags” (native whites who had joined the Republican Party), the Freedmen began to exercise almost complete dominance of local and state government. At the same time the native white citizens, intimidated by the occupying federal troops, were militarily and politically dominated by what they perceived as corrupt Republican administrations imposed upon them by the bayonets of their former enemies.

The Red Shirt Campaign of 1876, largely orchestrated by Martin W. Gary and M. C. Butler of Edgefield, was a massive organized effort on the part of the native white population to re-secure its control of the political machinery of the state. Violence was a calculated part of the strategy to remove Republican dominance. The Freedmen and their Republican allies tried valiantly to maintain their political control in the face of the fierce campaign by the former Confederates. By the middle of 1877 the Red Shirt strategy, along with an increasing willingness on the part of the rest of the nation to allow the South to go forward on its own terms, proved successful in bringing the control of the state back into the hands of the native white population. In the ensuing decades the black population of Edgefield, like that of the entire South, was thrust back into second class citizenship by the persistent efforts of the native whites who were determined to see that the conditions of Reconstruction were never allowed to return.

One of the principal results of the breakdown of the antebellum plantation system was that goods were no longer purchased centrally by the planters and then parceled out during the year, but rather Freedmen and other small farmers purchased their own goods as they saw fit. This, together with the proliferation of manufactured consumer goods in the late nineteenth century, led to the development of a vigorous commercial economy in which every town and every crossroads sprouted new merchants. These new merchants, who often used questionable practices to benefit themselves at the expense of their customers, enjoyed a long period of prosperity.

During this period the Village of Edgefield suffered a series of fires which destroyed practically all of the commercial area of the town except for the Court House. In 1881 and 1884 the entire eastern and northern portions of the town were laid waste in devastating fires. In 1892 the southern and western sides of the Public Square were burned. A Town Ordinance was passed in 1884 requiring that all new buildings constructed within 500 feet of the Town Square be built of brick. It was from the ashes of these tragic fires that most of the current buildings of the town were raised. Prosperous merchants and other town leaders built new stores and, in many cases, they built grandly. The commercial district around the Public Square and down Main Street began to take shape.

The continuing development of railroads, such as the Charlotte, Columbia and Augusta Railroad built through the eastern part of the County in the late 1860’s and the Augusta and Greenwood Railroad built through the western part of the County in the 1880’s, resulted in the development of numerous railroad depot towns, including Ridge Spring, Ward, Johnston, Trenton, Clark’s Hill, Modoc, Parksville, Plum Branch and McCormick. These new towns took on a prosperity of their own and began to sap commercial activity which might otherwise have come to Edgefield.

During this same period, the movement to bring government closer to the people resulted in the creation of a number of new counties, four of which took substantial portions of Edgefield. Aiken County was created in 1871; Saluda in 1895; Greenwood in 1897; and McCormick in 1916. Edgefield County, the area serviced by the Courthouse Village, was reduced in size to just over a quarter of what it had been.

The County’s agricultural economy began to suffer in the 1880’s. The combination of a dramatic increase in the production of cotton, the continued depletion of the rich soils of the piedmont regions of the County and other general economic ills which were also affecting farmers throughout the nation, made farming increasingly difficult. One Edgefield farmer decided to do something about these problems. Benjamin Ryan Tillman, believing that the state’s political leaders were not doing enough to help the farmers, instigated the farmers’ revolt, got himself elected Governor in 1890 and turned out of office the old Guard of the state, including the principal leaders of the 1876 Red Shirt Campaign.

In 1898 the Spanish American War broke out and a number of Edgefieldians became involved in the war effort. Former Confederate General and United States Senator Matthew Calbraith Butler received a commission as a major general in the United States Army. Former Governor John Gary Evans was commissioned as a major and inspector general in the army and afterwards became the civil administrator of the city of Havana. Edgefield lawyer and later Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina, James Hammond Tillman, was commissioned as a Colonel. Hundreds of other Edgefieldians served in the army in this very brief war.

In the thirty-odd year period from the late 1880’s through the early 1920’s a number of positive developments took place in Edgefield. The railroad finally reached Edgefield, the first telephone was installed, the Edgefield Mill was constructed, the first automobile came to town, electrical power was installed, water and sewer systems were built, a new hotel was constructed and the streets around the Town Square were paved. The town’s population had exploded, going from approximately 500 in 1880 to 2,500 by 1920. Edgefield, it seemed, was finally getting back on its economic feet.

In 1917, the United States entered World War I and many Edgefieldians were called upon to serve in the armed forces. A number of our Edgefield soldiers – white and black – distinguished themselves and received medals for their heroism. Sadly, twenty-five Edgefieldians died in the war, including eighteen blacks and seven whites. At home, the South Carolina economy boomed during the war with cotton demand and prices reaching highs not seen since the War Between the States. Cotton acreage and production continued to increase. The economic prosperity of Edgefield County for the foreseeable future seemed assured.

Unfortunately, beginning in 1921 and 1922, the boll weevil, which had come from Mexico and had been marching across the South since the turn of the century, finally arrived in Edgefield County, devastating the cotton crop on which the economy was almost entirely based. Farmers saw their production of cotton plummet by as much as 90 percent. Lands which had been devoted to cotton for more than a century were allowed to go idle. Sharecroppers, no longer able to make a living, left the farms and many left the state. Throughout the 1920’s farm incomes sank; merchants, unable to collect accounts from destitute farmers, were squeezed; banks failed. Then, when it seemed as if economic conditions could not get worse, the 1929 market crash and the Great Depression further impoverished the County. The population of Edgefield County began to decline and continued to decline in every census from 1920 to 1970.

World War II brought changes of other kinds. Young men throughout the County entered the service. A number of Edgefield families contributed multiple sons to the war effort. Former State Senator and Circuit Judge Strom Thurmond, West Side native J. L. Doolittle, Trenton native Fritz Huiet and Johnston native Robert Herlong all participated in the Normandy invasion. Women back home took on jobs which had traditionally been held by men. Rationing significantly affected everyone who remained in Town.

After the War, the soldiers returning brought back with them a new confidence and an ambition to improve the County. A well-organized effort to bring new industry to Edgefield enjoyed moderate success as the Crest Manufacturing Company was brought to Town in the late 1940’s. The neighboring town of Johnston was more successful as it secured both the Milliken and Riegel plants during the 1940’s and 1950’s. In the 1960’s Edgefield added to its list of new industrial recruits the National Cabinet Company, Star Fibers, Federal Pacific Electric and Tranter, each bringing a substantial number of new jobs. During this same period, farmers on the eastern side of the County began to expand their production of peaches which, by the 1960’s, had become nationally significant.

African American soldiers had also fought valiantly in World War II, and when they returned, they came with a determination to improve their status in American society. A sustained campaign for Civil Rights developed at a national level in the late 1940’s. The primary focus of this campaign was to overturn the institution of segregation which had been legitimized by the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson decision of the United States Supreme Court. In 1954 the Court, in its unanimous Brown vs. Board of Education decision, reversed the earlier decision and ruled that segregation was inherently unequal.

The white population of Edgefield, as throughout the South, reacted with outrage against the Civil Rights movement. The institution of segregation was deeply ingrained in society, and white Southerners were greatly offended by what they perceived as outside interference in their state and region. In 1948 in a campaign designed to send a message to the national Democratic Party, Governor Strom Thurmond became a candidate for President of the United States on the State’s Rights Democratic Party ticket and won five states and thirty-nine electoral votes. In 1954 recognizing the need to do something to counter the legal assault on segregation, South Carolina Governor James F. Byrnes initiated an effort to build new school buildings for the African American students. The construction of what is now the W. E. Parker School was part of that effort. Despite all the resistance the white establishment could muster, school desegregation proceeded in 1965 under the “freedom of choice” system and full desegregation followed in the fall of 1970.

The late 1960’s and the early 1970’s brought other new developments to Edgefield: a new water line capable of supplying the County for decades to come, a new country club, a new private school, a new County hospital, the National Wild Turkey Federation headquarters and a new congressman, Butler C. Derrick, Jr. For the next twenty years, from 1975 to 1995, Edgefield was perhaps the only town of its size in America which could legitimately claim to be the home of both a United States Congressman (Derrick) and a United States Senator (Thurmond).

In 1974, Dr. Thomas C. McCain, a black Edgefield County resident who had earned a Ph.D. at Ohio State University, brought a lawsuit in Federal Court against the county to force the county to implement single-member districts for its local elected offices. After nearly a decade, the suit wound up before the United States Supreme Court which ruled unanimously in favor of the Plaintiffs.

In the fall of 1984, the first election with single-member districts was held pursuant to the federal court’s orders. Of the five county council districts, three districts elected black council members. With its three-to-two black-majority on the council, the council elected Willie Bright, a black AT&T technician and part-time entrepreneur, to be the chairman. The council then fired the long-time white county administrator and the county attorney. A month later they hired Dr. McCain, whose lawsuit had brought about the change, as administrator. White citizens throughout the County were appalled and expected the worse to happen.

However, the black councilmen proved to be very moderate on substantive issues and Dr. McCain proved to be an able and fair administrator. The overwhelming majority of issues to come before the county council had nothing to do with race and the white members of council found that their black colleagues agreed with them on most issues. In the election of 1986, two years after the initial election of black council members, a white man was elected in the place of the black woman who had formerly occupied the seat. The county braced for what might happen next, but much to the credit of the white-majority council members, Dr. McCain was retained as administrator and Mr. Bright as county council chairman. Single-member districts were also mandated for other local offices, and blacks began to be elected to the school board and other county boards.

The U. S. Census estimates for 2018 show a population for Edgefield County of 27,052, with whites accounting for 61.7% of the total and blacks 35.7%. Race relations in the county over recent decades have generally been good, as confirmed by Dr. McCain in a 1987 interview: “You hear talk about the county being polarized. There’s no truth to that at all. People in this county have respect for each other.” As long as that continues to be the case, the county’s future should be bright.

Contact Us

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.